Summary¶

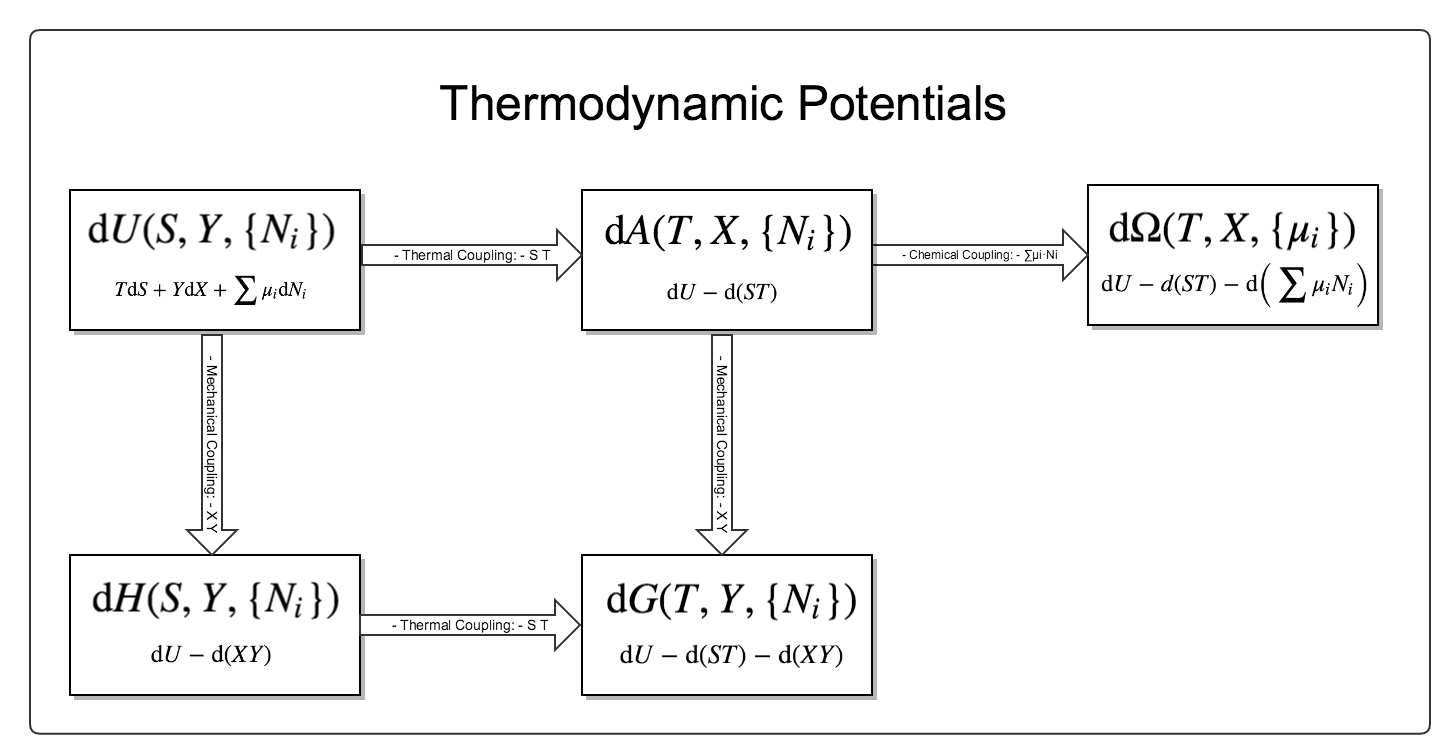

Thermodynamic Potentials¶

The first thermodynamics potential we will investigate is the (differential) internal energy \(U\). By definition, the internal energy is a function of entropy \(S\), volume \(V\) and number of particles \(N_i\), i.e.,

where repeated indices are summed over as in Einstein’s summation convention. The simplest way to generate all the other thermodynamics potentials is to use Legendre transform, which is explained in Legendre Transform.

Mathematically, a three-variable function will generate seven extra functions through Legendre transform. The differential forms of them are

Physically, there are three different kinds of couplings here, which are

- thermal coupling: \(d(ST)\);

- mechanical coupling: \(d(pV)\);

- chemical coupling: \(d(\mu_i N_i)\).

Legendre transform is about turning on and off switches of the three different couplings. For example, turning off the mechanical coupling of (differential) internal energy \(dU(S,V,\{N_i\})\) leads to (differential) enthalpy \(dH(S,p,\{N_i\})\). Indeed, enthalpy is the same as internal energy when we are talking about constant pressure.

To summarize, we have

- Internal Energy \(U(S,V,\{N_i\})\),

- Enthalpy \(H(S,p,\{N_i\})\),

- Helmholtz Free Energy \(A(T,V,\{N_i\})\),

- Gibbs Free Energy \(G(T,Y,\{N_i\})\),

- Grand Potential \(\Omega (T,X,\{\mu_i\})\).

Their relations are charted in Fig. 5.

Here are a few interesting points.

- All the thermodynamic observables can be obstained by taking the derivatives of thermodynamic potentials.

- Using this chart and 1, we could easily derive the Maxwell relations by using the Schwarz’ theorem.

The Sixth Potential?

Question: It seems that we can construct the sixth potential mathematically. It should appear at the right bottom of Fig. 5. Why don’t people talk about it?

Now we define this new potential and call it \(f(T,X,\{\mu_i\})\). The value of this function is actually zero. So we can have the derivitive of this potential which is also zero. This is the Gibbs-Duhem equation.

In the language of differential forms, we have \(\mathrm d\mathrm d f = 0\) where f is exact.

Hint

Question: Why is internal energy \(U\) a function of three extensive quantities, \(V\), \(S\), \(N\)?

We can start with any of the thermodynamic potentials and perform Legendre transform. Then again, we will get all the potentials. Then again we just have to name them. This function \(U(V,S,N)\) is just being named as internal energy.

Of course we mean something when we use the words ‘internal energy’.

Differential Forms¶

It is quite confusing to have so many potentials. We do have a mathematical theory called differential forms that make it easier to understand them.

What Are Forms

In simple words, 1-forms are linear mapping of functions to numbers.

For illustration purpose, we take the simple case that

We know that \(dU\) is a 1-form and it can be the basis of 1-forms, so is \(dV\). Also notice that we could define a map from a point \((U,V)\) to a real number, which explains the pressure \(p(U,V)\). As a result, \(\bar dQ\) is also a 1-form. Rewrite the equation using the language of forms,

where the under tilde denotes 1-form. However, \(\underset{^\sim}{\omega}\) is not exact, which means that we do not find a function \(Q(U,V)\) on the manifold so that \(\mathbf{d d }Q = 0\). Following Bernard Schutz in his Geometrical Methods in Mathematical Physics, an exact \(\underset{^\sim}{\omega}\) means that

where we have used the condition that \(\underset{^\sim}{dU}\) is exact, i.e., \(\mathbf{d}\underset{^\sim}{dU}=0\). For it to be valid at all point, we have to require \(\left( \frac{\partial p}{\partial U} \right)_V=0\) at all points on the manifold.

Frobenius’ theorem tells us that we will find functions on the manifold so that \(\underset{^\sim}{\omega}=T(U,V)\mathbf{d}S\), which gives us

if we have \(\mathbf{d}\underset{^\sim}{\omega} \wedge \underset{^\sim}{\omega}=0\), which is easily proven to be true here since we have repeated basis if we write it down (no n+1 forms on n-dimension manifold).

Or if we are back to functions,

With the help of differential forms, we could derive the Maxwell identities more easily. We start with the exterior derivative of equation (6),

Maxwell identities are obtained by plugging in \(T(S,V)\) and \(p(S,V)\) etc [VShelest2017].

How could this formalism help us understand more about the laws of thermodynamics, apart from the beauty of mathematics? As an example, we examine the second law using differential forms. Suppose we have a composite system, we write down the 1-form about the heat production,

We do not find global heat function \(Q\) and work function \(W\) on the whole manifold , i.e., we do not find a 0-form \(Q\) so that \(\mathbf dQ\) is \(T\mathbf d S\) [BSchutz].

We then consider the geometrical meaning of 1-forms. On a surface that describes the values of a potential, 1-forms are like equipotential lines. We think of a surface that describes the values of internal energy, where we find equi-entropy lines and equi-volume lines. One of the aspects of the second law is thus to state that for a system without heat exchange, the dynamics of the system is restricted to be only in a certain part of the manifold, i.e., it has limited states compared to the whole possible states on the manifold. In the language of differential forms, the second law is all about the existance of entropy (Caratheodory’s theorem).

The Laws of Four¶

Zeroth Law of Thermodynamics

Zeroth Law: A first peek at temperature

Two bodies, each in thermodynamic equilibrium with a third system, are in thermodynamic equilibirum with each other.

This gives us the idea that there is a universal quantity which depends only on the state of the system no matter what they are made of.

First Law of Thermodynamics

First Law: Conservation of energy

Energy can be transfered or transformed, but can not be destroyed.

In math,

where \(W\) is the energy done to the system, \(Q\) is the heat given to the system. A better way to write this is to make up a one-form \(\underset{^\sim}{\omega}\),

where in gas thermodynamics \(\underset{^\sim}{W}=-p\mathbf{d}V\).

Using Legendre transformation, we know that this one form have many different formalism.

Second Law of Thermodynamics

Second Law: Entropy change; Heat flow direction; Efficieny of heat engine

There are three different versions of this second law. Instead of statements, I would like to use two inequalities to demonstrate this law.

For isolated systems,

Combine second law with first law, for reversible systems, \(Q = T \mathrm d S\), or \(\underset{^\sim}{\omega}=T\mathbf{d}S\), then for ideal gas

Take the exterior derivative of the whole one-form, and notice that \(U\) is exact,

Clean up this equation we will get one of the Maxwell relations. Use Legendre transformation we can find out all the Maxwell relations.

Second Definition of Temperature

Second definition of temperature comes out of the second law. By thinking of two reversible Carnot heat engines, we find a funtion depends only a parameter which stands for the temperature like thing of the systems. This defines the thermodynamic temeprature.

Third Law of Thermodynamics

Third Law: Abosoulte zero; Not an extrapolation; Quantum view

The difference in entropy between states connected by a reserible process goes to zero in the limit \(T\rightarrow 0 K\).

Due to the asymptotic behavior, one can not get to absolute zero in a finite process.

The Entropy¶

When talking about entropy, we need to understand the properties of cycles. The most important one is that

where the equality holds only if the cycle is reversible for the set of processes. In another sense, if we have infinitesimal processes, the equation would have become

The is an elegent result. It is intuitive that we can build correspondence between one path between two state to any other paths since this is a circle. That being said, the following integral

is independent of path on state plane. We imediately define \(\int_A^B \frac{\mathrm d Q}{T}\) as a new quantity because we really like invariant quantities in physics, i.e.,

which we call entropy (difference). It is very important to realize that entropy is such a quantity that only dependents on the initial and final state and is independent of path. Many significant results can be derived using only the fact that entropy is a function of state.

- Adiabatic processes on the plane of state never go across each other. Adiabatic lines are isoentropic lines since \(\mathrm dS = \frac{\mathrm dQ}{T}\) as \(\mathrm dQ = 0\) gives us \(\mathrm dS = 0\). The idea is that at the crossing points of adiabatic lines we would get a branch for entropy which means two entropy for one state.

- No more than one crossing point of two isothermal lines is possible. To prove it we need to show that entropy is a monotomic equation of \(V\).

- We can extract heat from one source that has the same temperature and transform into work if the isoentropic lines can cross each other which is not true as entropy is quantity of state. Construct a system with a isothermal line intersects two crossing isoentropic lines.

- We can extract heat from low temperature source to high temperature source without causing any other results if we don’t have entropy as a quantity of state.

Irreversiblity¶

This problem can be understood by thinking of the statistics. Suppose we have a box and N gas molecules inside. We divide it into two parts, left part and right part. At first all the particles are in the L part. As time passing by the molecules will go to the R part.

The question we would ask is what the probablity would be if all the particles comes back to the L part. By calculation we can show that the ratio \(R\) of number of particles on L part and R part,

will have a high probability to be 0.5, just as fascinating as central limit theorem.

Gas¶

- Van der Waals gas \(\left( p + \frac{a}{V^2} \right) (V - b) = R T\).

Refs & Notes¶

- A Modern Course in Statistical Physics by L. E. Reichl

- Phase Transitions @ Introduction to Statistical Mechanics